The cultural appropriation of ikigai

How purpose became a Venn diagram

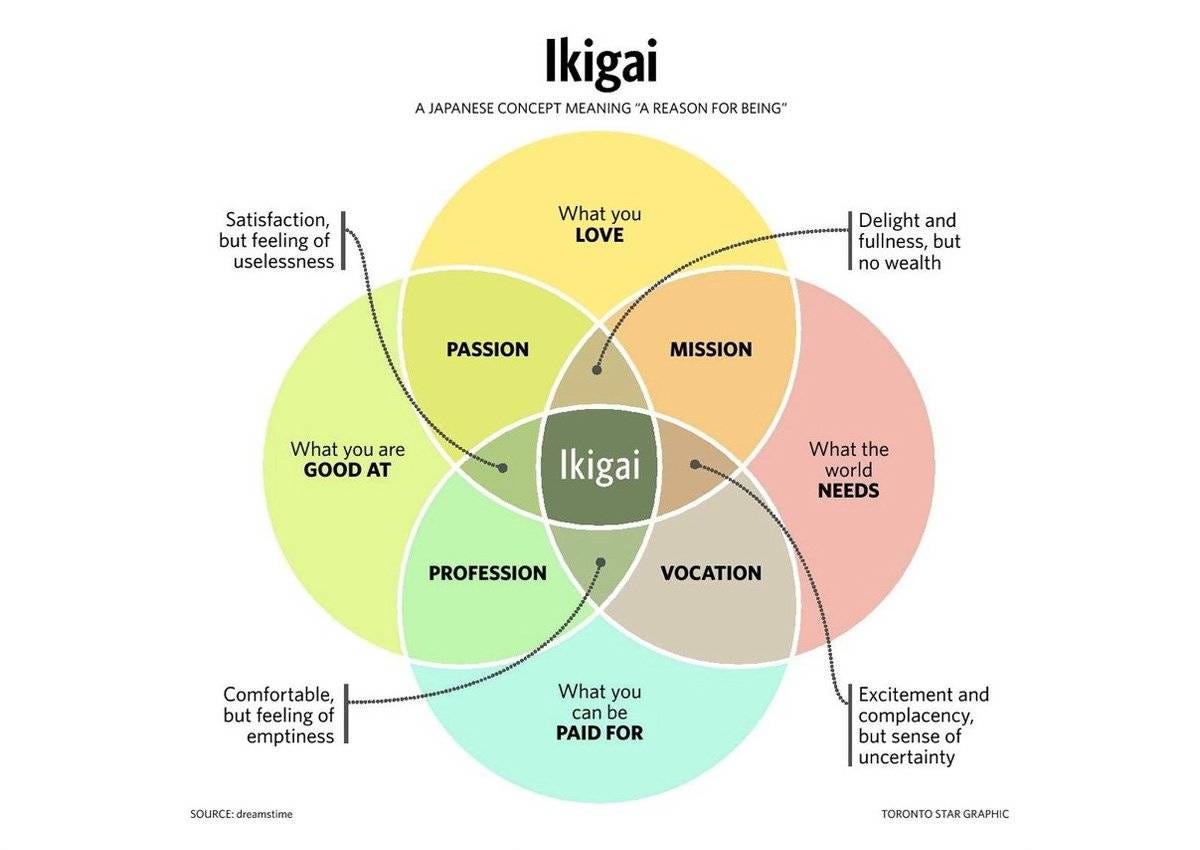

You have probably seen some version of this colorful graphic that shows purpose – labeled as ikigai – existing at the intersection of these four things:

What you’re good at

What you love to do

What the world needs

What you get paid for

It makes a cute meme – a simple framework, one that is easily repeatable – the idea that we discover the meaning of life by filling in four circles on a Venn diagram and then solving for the overlap. There is something so satisfying about purpose being something you can simply diagnose with this map.

The reality of what we refer to as “purpose” is much simpler than that. At least in concept. But there’s the concept, and then there’s the actual practice. It is the daily devotion to living on purpose that requires attention and effort, as I wrote about in Regenerative Purpose. But this piece is not about that. Rather this essay is a deeper dive into why this whole ikigai thing is largely a load of BS.

When I was writing my book, I interviewed a friend who is a professor of East Asian Studies at Harvard. In that interview, I found out a few things about ikigai, that are not commonly known.

On the etymology of ikigai

The first thing that I learned is that ikigai is not a traditional word in Japanese. In fact, there’s no such thing as ikigai in any ancient classical Japanese text. You will not find it used in that context at all. Of course, that doesn’t mean ikigai has no meaning.

Ikigai is now a term that is popularly used and holds meaning for many, far beyond the Japanese diaspora. The meaning in common usage today most closely mirrors that of raison d’être — which translates literally to “reason for being” in French. However, it’s a word that has entered the lexicon relatively recently. Kind of like “YOLO” (you only live once) or “Internet troll” or “vibe check”.

In other words, if you took a time machine back two generations and started talking about ikigai, no one would have any idea what you were talking about.

It is a modern mash-up of two words: the word iki meaning “life or way of living” and the word gai meaning “a real world effect or impact”. In traditional Japanese literature, the concept of gai was mostly used in a negative context, as gai nashi – a negation of the word that refers to something ineffective, useless or futile.

So the word ikigai is a modern amalgam that literally means “the result or effect of having lived”. It has been defined as an experiential quality in one modern Japanese-English dictionary, which describes ikigai as having the feeling that it's good that “I” was born. It is the impression that your existence is a positive thing.

On ikigai entering pop culture

The second interesting thing that I learned is that ikigai first became widely known in the world of medicine, as part of a naturopathic treatment of cancer. It did not originate within the sphere of personal growth or psychology.

In the 1920’s, there was a Japanese doctor interested in naturopathic treatments of cancer and other terminal diseases. He believed that fear of death and anxiety led to worse health outcomes for those living with these illnesses. His thinking, which was quite uncommon at the time, was that these common negative emotions actually feed the illness. To counteract that, he wanted his cancer patients to cultivate a sense of value in being alive.

This doctor encouraged his patients to accept their illness and say: “My life has value, I’m going to live my life to its fullest.” He wanted them to actively embrace their lives rather than giving up and just passing the time. He guided them to determine what gave them the most fulfillment in life, as part of their treatment. It was known as ikigai ryoho or ikigai treatment.

Other doctors who were influenced by him carried on with this kind of naturopathic treatment. In the 1980s, one of them led an expedition of cancer sufferers in climbing Mont Blanc in France. Mountain climbing is a big deal in Japan, and it is associated with having a healthy vibrant life. So this was a big turnaround from the image of cancer patients staying in a hospital bed receiving treatment. Instead, these patients were saying, “Let me embrace my life fully; I'm going out into nature to do something difficult.” There have been many similar expeditions on Mount Fuji since then, which often get a lot of attention on Japanese television. This is probably how the idea of ikigai started to seep into broader consciousness.

On how ikigai relates to the four dimensions

The third thing that I learned is that the four dimensions mentioned in the modern-day Venn diagram purpose model actually have no basis in Japanese cultural history. Yup. You read that correctly. Zero.

Again, don’t take my word for it. This is according to a Harvard professor who has dedicated nearly thirty years of his life to studying these things.

So when – and why – did the manufactured term ikigai become synonymous with a four-part Venn diagram depicting the elemental components of one’s purpose for existence on Earth? The answer is we don’t know.

We don’t know exactly when this emerged as a meme in collective consciousness. Internet histories are almost as difficult to trace as oral histories since claims of authorship are rarely investigated or substantiated.

We also don’t know why it became popular. My professor friend Dr. Atherton has some theories on this, which I will leave you with. Here is what he says:

“These days there seems to be a real fascination with — or even fetishization of — Japanese terms in general. Every week I see a new smartphone app that takes its name from some exotified Japanese word. The creators take a random Japanese term and spell it kind of funny or somehow make it sound futuristic. I think it’s because Japan occupies a special place in Western imagination. It has an interesting combination of being futuristic and also having a minimalist aesthetic, which pairs nicely with the modern tech world. Take that, along with the Japanese language, which is written phonetically and therefore easy to pronounce for English speakers; yet at the same time it has an exotic sound to it. It is a fetishized version of a certain Japanese aesthetic that's partially connected to the past, but for the most part it is BS.”

If you want to know more about how the simplified four-part Venn diagram can be expanded upon and come alive as a map for awakened, purposeful living, you can read or listen to my book, Regenerative Purpose. It is downloadable for all e-readers as well as available in an audiobook version.

To support my work as a writer on an ongoing basis, please consider sharing this essay if you found it valuable, or join my Substack as a free or paid subscriber. Not ready to subscribe yet? You can always buy me a coffee.